2002: The Great Reset

In 2000, the music landscape was bleak. Nu-metal dominated the airwaves. Skate-punk fashion was rife. The UK had lost its edge and was in the shadow of a wave of toxic masculinity and god-awful sound and fashion of nu-metal and skate punk.

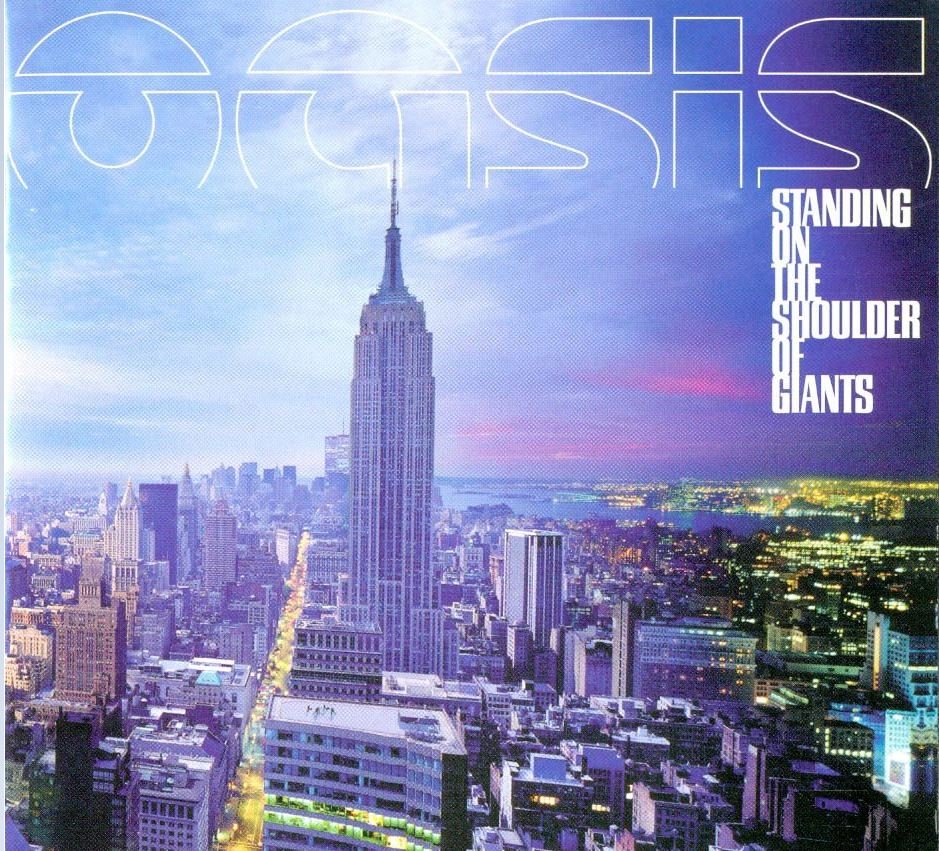

‘Standing On The Shoulders Of Giants' endured rather than thrived. ‘Gas Panic’ and ‘Fucking In The Bushes’ were fleeting moments of brilliance amid a sea of dross. If they had embraced Noel’s cold turkey writing via ‘Cigarettes in Hell’ and ‘One Way Road’ would have at least given the UK’s cocaine hangover an interesting perspective.

It wasn’t just Noel all at sea. In 2001, the revolutionary class of 1994 and bombast of 95 & 96 was all fading in some form or another. The Manics, Supergrass, and Ocean Colour Scene all produced underwhelming albums. Shed Seven, who did find their punk spirit on their ‘Truth Be Told’ were being marginalised and forced out of a scene they once lit up from the periphery.

Something needed to change to make Neil Young right.

In 2001 The Strokes blew up with their garage rock classic ‘Is This It?’ and rightly took all the plaudits. Meanwhile, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club and Soundtracks Of Our Lives kept the flame alive for rocks heritage with great albums. Alas, it never felt enough for British hearts and minds. The reference points and fashion were ever so slightly out of reach. For most, they were too cool for our feral shores. It meant rocks pendulum remained in the US.

However, in March via West Birmingham, one man was going well beyond the concept of resetting rock ‘n’ roll. Mike Skinner was rewiring hip-hop and dance music. Inspired by MJ Cole’s fine ‘Sincere’ album in 2000, Skinner took the worthiness of Ken Loach to the benign garage scene to conjure art for the ages.

‘Turn The Page’ and ‘Original Pirate material’ stripped everything back to MJ Cole’s meaningful vision of the scene. Skinner’s unique vocal delivery consigned a plague of West Coast wannabees to the bin. It went beyond garage music though, he conceptualised weed smoker philosophy with Ray Davies’ sense of characterisation and storytelling (‘Too Much Brandy’ / ‘Same Old Thing’). ‘Stay Positive’ was a desolate uncertain tale of a friend trying to keep fellow souls from drug and violent descent. It was the trailer to the great British grime phenomena coming via Dizzee in 2003 and Kano in 2005. It culminated in ‘Weak Become Heroes’, his ode to raves and ecstasy. Reigniting the second summer of love and rave culture in a Blake-esque poem in 2002, when Blairism was motoring toward PFI contracts and corporatism was a great cultural moment. It signified a generation uneasy with the power being wielded and, if pushed too far, would force escape through drugs and music once more.

Never to be left out of any scene, Liverpool was preparing to release psychedelic folk punk onto the airwaves. On April 17th, The Coral signed to Deltasonic and played Dingwalls and thus, turned their lives upside down. Noel Gallagher talked of that day to Jools Holland in lockdown:

“this band were playing at dingwalls…these lads walked on stage and they were kids. They were so young that they’d signed their record deal that day but their parents had to sign it for them and they played this song, it sounded like Frank Sinatra meets The Who meets Burt Bacharach…”

James Skelly’s unfettered vocals alongside Bill Ryder Jones and Lee Southall’s guitars were beautifully jarring. They had the ability to take Beefheart to the studio with Bacharach and Costello. Like Skinner, their talent was obvious, ‘Dreaming of You’ was an instant pop classic, but it was their beatnik fuck everyone attitude that shone brightest. British bands were supposed to make verse, chorus verse solo outro songs. ‘Waiting For Heartaches’ toyed with tempo and big key changes like an Arthur Lee wet dream. ‘I Remember When’ sees Skelly’s raw Roger Daltrey vocals front up a psychedelic sea shanty, whilst ‘Simon Diamond’ took Syd Barret’s psyche-folk out for a walk with Karen Carpenter. Perhaps more than most that year, they embodied what youth can do for the soul. Unaffected by failure, they reinvented what Mod could be their untamed debut.

Across the Pennines in Leeds, The Music, the most overlooked during 2002’s great reset, were led by break dancing front man Rob Harvey who later joined The Streets and Kasabian. Their self-titled debut, like The Coral, looked not to merge their disparate influences but, to smash them into oblivion a la Jackson Pollock and see what stuck. The space rock of The Verve, Robert Plant’s bewitching vocals, and Nile Rodgers licks flirted with electronica and the early hiss of Oasis on this wild adventure. They fixed the failures of the Roses ‘Second Coming’ and they injected The Verve’s ‘Storm In Heaven’ weightlessness with a punky outlier spirit courtesy of Adam Nutter’s guitars.

While the nods to the past were apparent, Robert Harvey’s vocals served up a purity so distilled it engaged a new generation of rock classicists. Coupled with his on-stage dancing, it gave fans a freeing impetus to clutch the band to their hearts and decree “this is ours”.

It was though, in the moments they made you dance they truly lifted the UK scene out of the doldrums. ‘Disco’ builds like early Ride before erupting into a psychotic bout of funk and soul. Moreover, ‘Float’ did what the Mondays and the Roses did so well in the 80s and tapped into the dance trend of the time; nu school breaks. Nailing the relentlessness and twitchiness of an Adam Freeland or Krafty Kuts set into 5mins of rock music was remarkable.

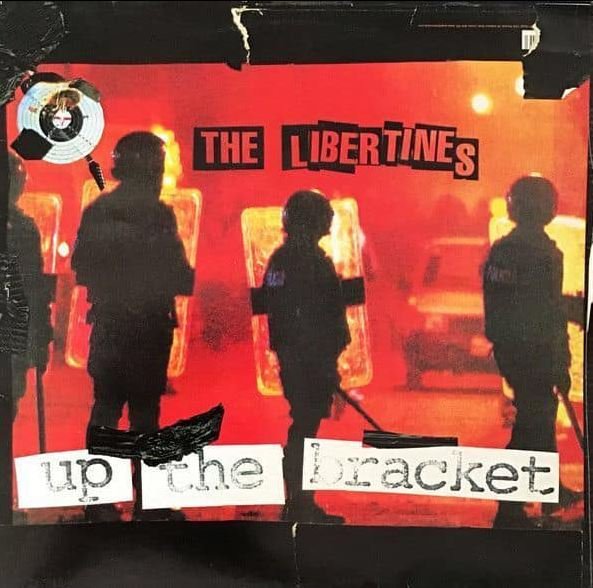

Then, on 14th October 2002, the axis of rock ‘n’ roll truly splintered into something new. The Strokes’ influence on The Libertines had been colossal. The band re-routed its power supply from John Hassall’s 60s flowery numbers to Pete and Carl’s Kinks via The Clash brutality tales of England. On hearing ‘This Is It’, Pete and Carl in collusion with Banny Poostchi, launched ‘Plan A’; an all-or-nothing mission to get them signed to Rough Trade in six months. After a showcase for James Endeacott, they were tipped to Geoff Travis and the rest was history.

The internet hadn’t really been a force for good in the music industry to this point. The Libertines, like many of the architects of Silicon Valley were dreamers though. Guerrilla gigs, invading Zoe Ball’s XFM show, house parties, and free tattoos in Soho were orchestrated from their blog and fan forums. Whilst other bands were all about the music, The Libertines went further. They created the community we yearned for. Much like the early 70s before punk, rock music had become bloated and out of reach for the common man. They took it back to the streets, literally on some occasions. They inspired people to pick up guitars and poetry books. They changed fashion, alas, they changed drugs.

Not that the music didn’t matter. The skill levels were down but the hope stakes were through the roof! The guttural sound from the guitars was so desperate, they were the catalyst for change culturally that millions were waiting for.

2002 saw the initiation of the war on terror. It was the inauguration of Blair’s descent. It left so many feeling dirty, sorrowful, and uneasy with their country’s place in the world. What The Libertines did was, remind the world what England could be. Dangerous but poetic. Unhinged but beautiful. Keats and Yates were on their side!

The landscapes and characters were familiar but the dreams were new. ‘Time For Heores’ spawned the greatest couplet since ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’:

“There's fewer more distressing sights than that

Of an Englishman in a baseball cap”

‘The Boy Looked At Johnny’ is arguably the best proponent of their back-and-forth vocals which were to become famous, infamous, and their harmonious over the course of 20 years. They sounded like a drunken night, staggering through the streets antagonising anyone who wasn’t with them (and Johnny Borrell). Pete’s ability to elevate a song with a fragile melody in the chorus was finding its feet here, something that he would go on to perfect but, all too infrequently.

“we set out to be as exciting as the Pythons”. (Rik Mayall talking to Wogan in 1984)

This eclectic bunch was the same. Like a great John Hughes movie, the youth just wanted to be heard! For music lovers, it was the raw reset filled with adrenaline and ecstasy the alternative scene needed. It spawned another 8 years of bands. Wave upon wave they came. The kids who flooded playgrounds with kickers and Mr. Spliffy jackets and had grown up and wanted their time and boy, they took it! It was, sadly, to be the last hurrah of the music industry paying bands properly. The well-worn social contract of., take your shot at glory and escape the doldrums was dissipating as the world raced to the bottom.

However, for one year, hope was everywhere. Psychedelic punks, social commentators, romantic poets, and riff makers alike came together to tear down the tired fabric of the rock industry as we knew it.